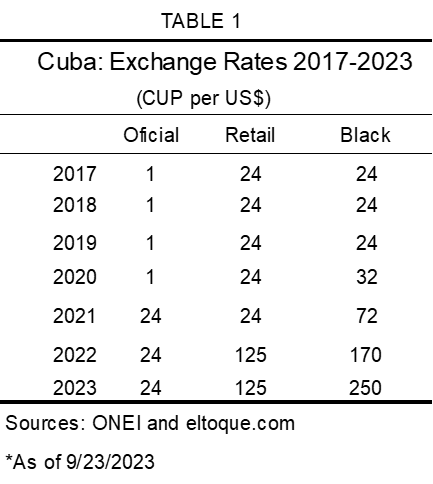

The black or informal currency market in Cuba is decades old. It took off spectacularly after the monetary reform or ordenamiento monetario in early 2021. The black market arises out of controls on foreign exchange movements and official exchange rates set at levels below the price needed to balance the market (Luis 2023). There is only a very small offer of dollars to the population at official rates. Thus residents access the informal market to meet dollar needs for many important goods and services including foodstuffs, medicines, travel and clothing. More recently small private businesses (MIPYMES) also use the informal market to obtain dollars for their operations. High inflation unleashed after the peso devaluation in early 2021 and sustained by a sizable fiscal shortfall goes a long way to explain the steep fall of the Cuban peso (CUP) against the dollar (TABLE 1). The black-market rate has fallen 247% since end 2021 and is now at CUP 250 as against CUP 125 for the official retail rate at exchange houses and CUP 24 used in government entities and state companies.

In this context it is important to understand the structure and workings of the informal market which has great relevance for the wellbeing of the population, the cost of living and the dynamics of inflation. This article presents initial research done from bid-offer notices in digital segments of the informal market provided by El Toque. The market comprises several segments. Its most important are the US dollar and the MLC which refers to the exchange for CUP of restricted dollar deposits in Cuban banks.

Outline of the Informal Market

The informal currency market is a decentralized market operating in social media and physically in the island and offshore. Hundreds of transactions take place independently every day. Bid and ask offers are made by participants in the web. It is a retail market largely involving transactions in the hundreds of dollars though it is reported that large transactions take place privately and are not seen in open social media. The size of the market is limited by two main factors. First, participants are persons and small business unlike in formal currency markets where financial institutions and large firms dominate trading. Transactions in the black market are linked to the needs of families for consumption, travel or investment while those linked to the import needs of MIPYMES are constrained by the low capitalization of small firms in Cuba.

Second, transactions are limited by restrictions to the flow of funds in the Cuban and US banking systems. There is a limit, for example, of MLC 1000 in digital bank operations in the Cuban banking system. More recently in 2023 limits on cash withdrawals from Cuban banks of CUP 5000 as part of the bancarizacion or digitalization of the banking system is affecting the black market (Vidal 2023 and Gaceta 2023). In addition US regulations ban the operation of American banks with entities in Cuba. Estimates of dollar transfers from the US to Cuba, information from market participants and US-Cuba trade flows suggest that the black market in Cuba is small compared to formal currency markets in neighboring countries. The size of the market is dependent on remittance flows and transactions from the stock of dollars and other foreign currencies in the island.

Market Making Activity

Data on bid-ask digital messages on the MLC segment of the market gathered by El Toque yield insights on market activity. The black market is a retail market used from time to time by most participants. However there are frequent participants which access the market for their own needs or on behalf of others. Size limitations mentioned above also result in multiple transactions to reach buying or selling amounts targeted by participants. Importantly, some frequent participants engage in market making activity, simultaneously buying and selling dollars or MLCs. The pattern of bid-ask messages by frequent participants helps to identify market making activity. Market makers are willing to buy or sell dollars continuously and show a pattern of simultaneous bid-ask messages. In this article I use a period of up to 24-hours of bid and ask messages by a single frequent participant as being “simultaneous”. In other words digital messages indicating willingness to sell and buy dollars at set prices by a participant are evidence of market making activity.

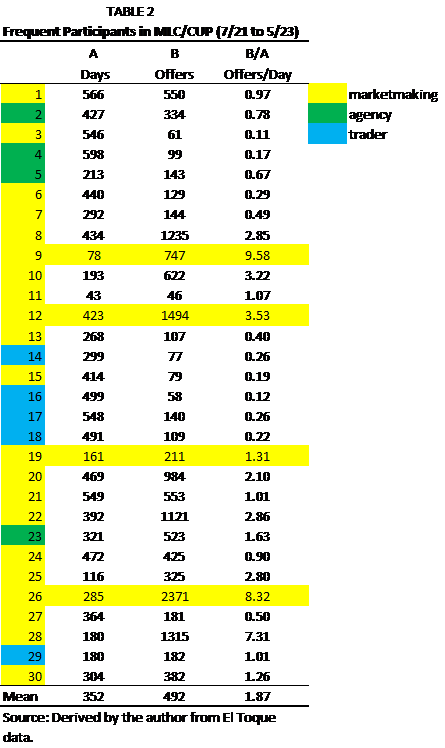

TABLE 2 shows patterns of market participation by the 30 most active participants in a sample of messages covering the period from July 2021 to May 2023. The sample comprises over

30,000 bid and ask offers in social media in the MLC/CUP market. Dollar cash activity is not covered by the data. The data provides insights about the behavior of market participants in one of the two important segments of the market.

The data shows that 21 out of 30 most frequent participants engaged in market making activity. This is marked by the yellow coloring on the left column of the table. However only 4 of the 30 (horizontal yellow line on TABLE 2) are dedicated market makers. Market making activity is evident from two-way participation in the market. The non-dedicated 17 participants engaged in market making but showed largely one-way offers indicating that they were buyers or sellers of MLC for sustained periods. This is consistent with “agency” activity to buy or sell MLC for their own use or on behalf of third parties. It is not possible to further identify agency activity. The institutional role of participants is not known. They may be acting as brokers on behalf of clients or acting for their own import needs in the case of MIPYMES. Other frequent market participants are engaged in trading, taking positions and realizing gains or losses for investment or speculation. It is not possible to estimate gains or losses as the data shows offers and not actual transactions. Traders have much lower market participation than average.

Overall frequent participants average less than 2 trading offers per day which is consistent with sticky pricing observed in the market. The most active dedicated market maker has 8.3 average bid and ask offers per day while the average for the four dedicated market makers is 5.7. This implies that only some transactions take place through dedicated market makers. Moreover the median bid-ask price in the CUP/US$ market shows low volatility. The annualized daily volatility of the median price is about 2% in the two years to May 2023, compared, for example with volatility of around 7% for the euro/dollar market, the world’s most active currency market. This means that even though the informal CUP/US$ rate devalues month to month the median rate is sticky day-to-day. Transaction data is needed to analyze further sticky pricing in the market.

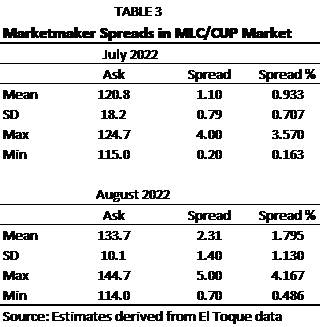

Analysis of bid-ask spreads of market makers sheds light to the structure of the informal market. TABLE 3 shows market maker spreads in July 2022 and August 2022. I selected these two months as an unexpected government announcement led to sharp movement of prices from an average of CUP 121 in July 2022 to CUP 134 in the following month in the MLC/CUP market and a comparable depreciation in the US$/CUP informal market. The depreciation followed an announcement by the Economics Ministry of a new retail dollar market in official CADECA exchange houses (EFE 2022). The sharp depreciation placed stress on market participants and market makers who were exposed to higher risk on currency inventory. As may be anticipated this was accompanied by a doubling of average bid-ask spreads from 0.9% to 1.8%. The range of spreads offered by market makers widened as well. Notice that average market maker spreads in the MLC segment of the informal market are moderate in historical perspective. This likely follows from widely available pricing information in social media. There is no comparable data for the dollar/CUP segment of the informal market. In some ways the MLC market is riskier than the cash dollar market as the former is subject to direct regulatory risk in the Cuban banking system.

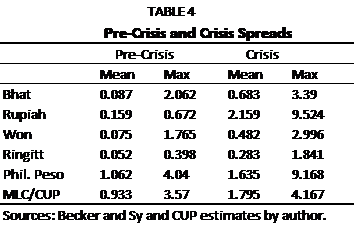

As a cross-check I compare bid-ask spreads in Cuba with those prevailing in floating currency markets in other developing countries (Becker 2005). TABLE 4 shows bid-ask spreads in the MLC/CUP market before and after the shock of August 2022 with spreads in formal markets of five Asian currencies before and after the 1997 Asian currency crisis. The pre-shock MLC/CUP mean spread of 0.9 % as could be expected is higher than the spread in four of the Asian currency markets and about the same as the Philippine peso. However, post-crisis maximum spreads in Cuba reached 4.2% and were significantly lower than in Indonesia and The Philippines. This implies that liquidity may not have been as strained in the Cuban black market as in some Asian floating rate markets. Cuba unlike Southeast Asia did not experience a banking crisis.

Market makers give structure to the foreign exchange market (Lyons 2001). Available data indicates that decentralized market making in Cuba provides a functioning structure for the informal market. Dedicated market makers are supported by occasional market making by other frequent participants. Resulting bid-ask spreads are reasonable in the light of information from formal markets studied in the literature.

CONCLUSION

The informal currency market in Cuba is longstanding and took off since 2021 after a failed monetary restructuring. Analysis of bid-ask data in the MLC segment of the market shows substantial market making activity. This gives structure to the market and helps explain the movement of bid-ask spreads. Spreads are within the range observed in developing formal currency markets. Price transparency in social media is a positive element for the informal market. Orderly trading in the informal market provides support for policy moves towards liberalization of Cuban currency restrictions.

REFERENCES

Becker, T. and A. Sy, 2005, “Were Bid-Ask Spreads in the foreign exchange market excessive during the Asian Crisis?” IMF Working Paper, WP/05/34, February 2005.

EFE, 2022, “Cuba cerca del techo de los 200 pesos por dólar en el mercado informal.” 3 de octubre.

Gaceta Oficial de la Republica de Cuba, 2023, 2 de agosto.

Luis, L, 2023, “Inflation and Macro Policies in Cuba.” Ascecuba.org/blog, January 6.

Lyons, R. K., 2001, The Microstructure Approach to Exchange Rates. Cambridge, MA, MIT Press.

Vidal, P.A.,2023, “El Banco Central de Cuba no entiende la demanda de dinero.” El Toque, 18 de agosto.